When Sylvia Plath’s first baby, Frieda, was born she wrote to her mother, “I couldn’t take my eyes off the baby. The midwife sponged her beside the bed in my big pyrex mixing bowl”. “I am itching to get writing again and feel I shall do much better now I have a baby. Our life seems to have broadened and deepened wonderfully with her.” In Sylvia’s Letters Home, compiled by her mother, her wonder and insistence on children as “an impetus” to her writing, on their power to provoke a capacious life, is a euphoric and valiant engagement with the project of working motherhood that gallops. A galloping feeling in the mind when I read her mothering accounts—a galloping affinity, and also the morbid gallop of the context of her death which each letter gallops us towards. When I was a teenager I wore the name “Sylvia” on a short silver chain around my neck. My Sylvia then was not a mother with a pyrex bowl.

But my Sylvia now eats veal casserole a neighbour makes her after labour; she is ready for nothing more concentrated than a pile of old New Yorkers—“first the jokes and cartoons, then the poems, then stories”; she has not “accomplished anything except feeding the baby and writing a few letters”; she’s worrying about the babysitter and the bottle so she can drink “champagne with the appreciation of a housewife on an evening off from the smell of sour milk and diapers” at Faber & Faber; she’s breastfeeding her baby in the car; she’s hungering for a study of her own “out of hearing of the nursery” where she can be alone with her thoughts for a few hours a day; she has “a poem about the baby in this month’s Atlantic”; she’s planning “an absolutely unsocial, quiet, hardworking winter”; she’s trying to pull her health up “from the low midwinter slump of cold after cold” by eating “big breakfasts (oatmeal, griddles, bacon, etc., with lots of citrus juices)…along with iron and vitamin pills”; her day is “a whirlwind of baths, laundry, meals, feedings”.

“I never dreamed it was possible to get such joy out of babies,” she writes.

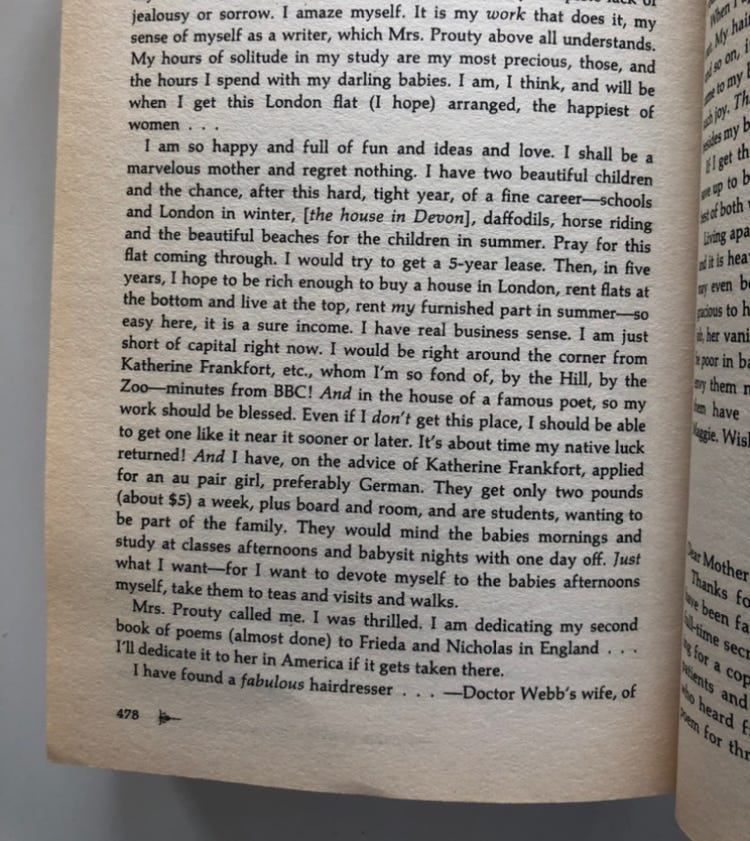

Sylvia’s final letters to her mother are doggedly repetitive and insistently inventive with visions of childcare: “I am getting estimates about rebuilding the cottage so I someday can install a nanny and lead a freer life”, “I must at all costs make over the cottage and get a live-in nanny next Spring so I can start trying to write and get my independence again”, “I got this nanny back for today and tomorrow. She is a whiz, and I see what a heaven my life could be if I had a good live-in nanny”, “first the cottage, then the nanny”, “if I had the time to get a good nanny, possibly an Irish girl to come home with me, I could get on with my life…I feel only a lust to study, write, get my brain back and practice my craft”, “could either Dot or Margaret spare me six weeks. I can get no good nanny sight unseen; I could pay board and room, travel expenses and Irish fares”, “know my only problems now are practical: money and health back, a good young girl or nanny, willing to muck in and cook, which I could afford once I got writing”, “do you suppose instead there is any possibility of your chipping in and sending me Maggie?…Do I sound mad? Taking or wanting to take Warren’s new wife? Just for a few weeks! How I need a free sister!”, “I love it here, even in the midst of this. I see it is imperative to have a faithful girl or woman living in with me, so I can go off for a job or a visit at the drop of a hat and write full time. Then I can enjoy the babies”, “I must have someone live in or otherwise I don’t eat and can go nowhere”, “I adore the babies and am glad to have them, even though now they make my life fantastically difficult. If I can just financially get through this year, I should have time to get a good nanny”, “I see now just what I need—not professional nannies (who are snotty and expensive) but an adventurous, young, cheerful girl (to whom my life and travel would be fun) to take complete care of the children, eat with me at midday”.

The need of “a free sister”, an adventurous girl to mind the babies for a few hours to get one’s brain back echoes like a black wind through the correspondence of mothers, through generations of women, each in their own privacies.

It’s particularly painful to me that this need was such a persistent bell in Sylvia’s last letters to her mother, because she had a robust and commodious vision of childcare that seems to understand better than anyone the complex feelings of being a mother committed both to their vocation and to their babies, who dreamed of an architecture for the day which might amiably contain both forms of labour and rapture:

A few letters later (to her aunt Dotty this time), she writes:

“I hope by the New Year to have this place pretty well furnished and cosy and get a mother’s help to live in by then. And then I should be able to really get on with my career. It is lucky I can write at home, because then I don’t miss any of the babies’ antics.”

I share Sylvia’s utopian dream of having the mornings to work, afternoons with the baby, and evenings out—a life where one’s vocation, one’s baby, and one’s social self might coexist. But during the week I miss a lot of the baby’s antics. I compress Sylvia’s vision of afternoons into Friday morning:

This precarious balancing of time—this improvising of time to work, time for children, time for romantic endeavour, time for reading, time for inner examination, time for friendship—how it preoccupies me.

“But I get strength from hearing about other people having similar problems,” wrote Sylvia.

HM.

thank you for this harriet, i love it

i really enjoyed this - thank you!